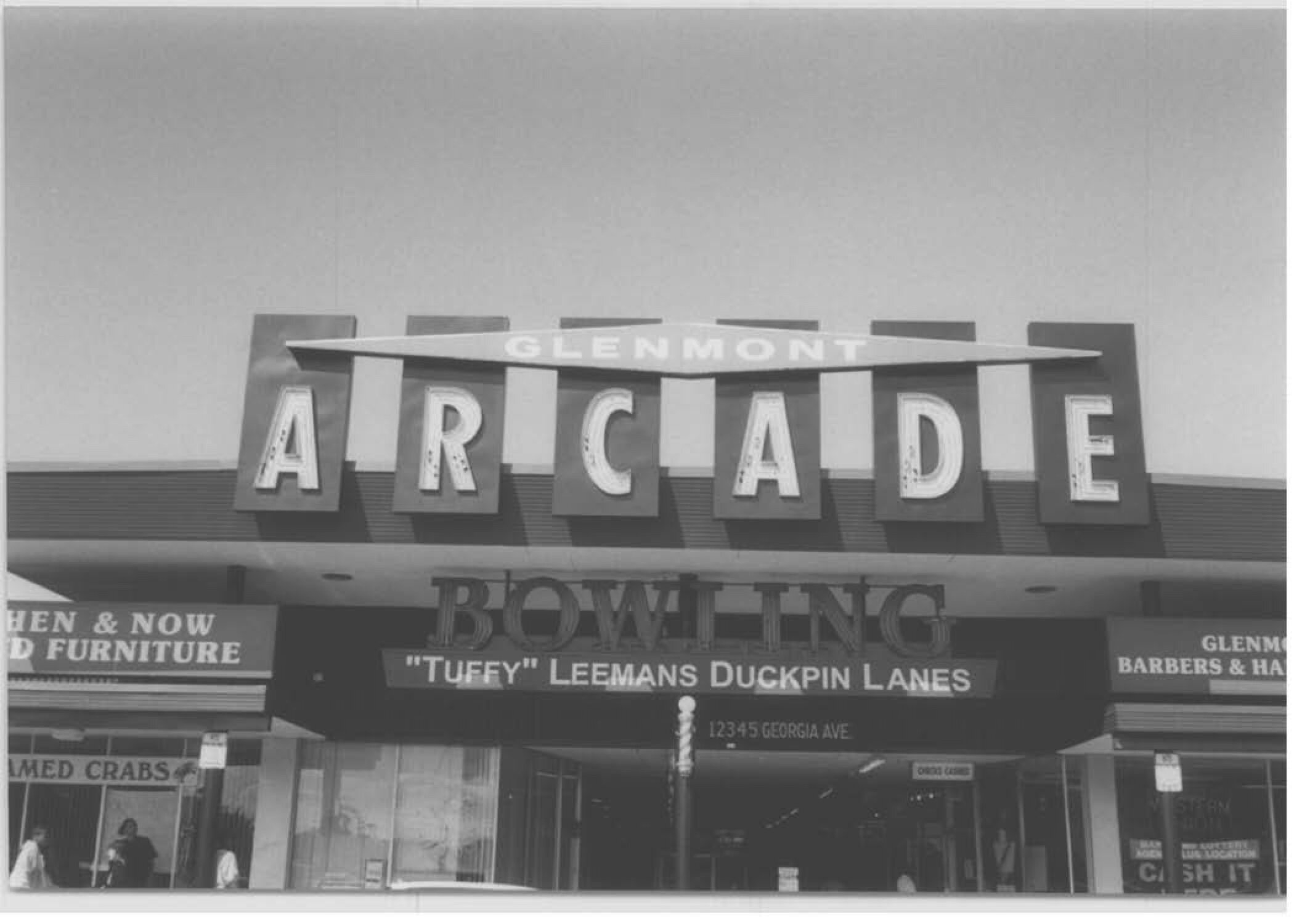

Glenmont Arcade, Glenmont, Maryland

Glenmont Arcade: A Touch of Googie Architecture in the DC Suburbs

Silver Spring, Maryland

Completed for the National Parks Service and currently is part of the Library of Congress holdings (HABS No. MD-1420) .

Significance

The Glenmont Arcade was constructed in 1960 as the largest, and most architecturally intriguing component among the original portions of the Glenmont Shopping Center (1958-60). The shopping center is representative of the history of commercial architecture and development in the post-World War II, or postwar, suburbs of Washington, D.C., and highlights changing middle-class values and tastes in the midtwentieth century. Developed in a piecemeal fashion with the intention of providing basic amenities to nearby neighborhoods and subdivisions, the Glenmont Shopping Center’s initial supermarket, drug store, and specialty stores were owned by several different entities that ranged from corporate chains to small local investors and business owners.

With disjointed ownership and development, the Glenmont Shopping Center struggled to find a unified appearance with the notable exception of the Glenmont Arcade at its eastern terminus. The design of the Arcade—a cohesive grouping of fourteen small shops located on either side of a broad, covered pedestrian circulation space—was based loosely on the typology of upscale commercial arcades of the nineteenth- and earlytwentieth centuries. It is an unusual instance of the form as it is located in a wholly caroriented suburban setting and is integrated into a conventional shopping center having storefronts and a covered, linear walkway facing out onto a large parking area. The Glenmont Arcade is also noteworthy for its superlative “Googie” stylistic elements, which are rare survivors in the Washington metropolitan area. It presented a modern, uniform façade to passing drivers, featuring angled floor-to-ceiling glass storefronts and brightly-colored, gravity-defying neon signs and overlapping planes typical of Googie design. A twenty-four lane bowling alley on the lower level, accessible via a set of stairs at the rear of the Glenmont Arcade, provided an entertainment component and a community center to the otherwise retail oriented facility. Among the original sections ofthe shopping center, the Glenmont Arcade was the most architecturally ambitious and unified and, despite numerous renovations to the rest of the shopping center, has retained nearly all of its character-defining stylistic and formal features and components.

Part I: Historical Information

A. Physical History:

1. Date of erection:

The Glenmont Arcade was completed in 1960, the final of four components individually constructed between 1958 and 1960 comprising the original extent of the Glenmont Shopping Center.

Architects:

Bartley & Gates (Glenmont Arcade)

John A. Bartley (1920-2010) was born in New Rochelle, New York. He attended Wake Forest College in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for three years before serving in the U.S. Marines Corps as an air navigator from 1942 to 1945, reaching the rank of captain. He entered the University of Virginia in 1946 and graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Architecture two years later. After working in Washington, D.C. as a draftsman at the firms of Mills, Petticord & Mills and J. Woodener Company, he was hired as an associate in the firm of Benjamin P. Elliott and subsequently partnered with H. Byron Gates (1921- 1994) in 1954. Gates, born in Elmira, New York, served in the U.S. Army in North Africa and Europe during World War II and received a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from Penn State University in 1949. Upon graduating, he also worked as a draftsman at the firms of Mills, Petticord & Mills and J. Woodner Company, where he likely met and worked with Bartley. Gates was the chief draftsman in the firm of Edmund W. Dreyfuss when he and Bartley launched their firm.

Mills, Petticord & Mills, the first firm in which Bartley and Gates worked together, was a local firm with commercial and institutional commissions of various scales in Washington, D.C. and its suburbs, including the original portion of the Belle View Shopping Center (1950), the Dupont Circle Branch of Riggs National Bank (1955), a youth correctional center in Lorton, Virginia (1954), an office building on 15th Street Northwest (1954), the Rural Electric Building at 20th and Florida Avenue Northwest (1956), and the eastern wing of the Natural History Museum, Smithsonian Institute (1956).4 J. Woodner Company, where both subsequently worked as draftsmen, was a building company involved mainly in residential construction along the Atlantic seaboard, both single-family houses and apartments.

This experience in both residential and commercial buildings no doubt aided the young firm in several of their early projects. Beginning in 1956, the Bartley & Gates worked with Kay Construction Company to design five different model houses for the Kemp Mill Estates in Montgomery County. The residences, predominantly ranches and split-levels, were comprised of three bedrooms and two bathrooms and could be purchased for $21,000 to $24,950. Bartley & Gates continued to design houses for Kemp Mill Estates throughout the late 1950s, winning an award from American Builder magazine in 1960 for their “Surbama Bali” house design, which featured a “wrap-around terrace” where the patio was surrounded by the family room, kitchen, entry hallway, and living room. The firm completed several commercial buildings in Wheaton including the Capri Restaurant (1958) and the Wheaton Bowling Alley (1958); the bowling alley, like Glenmont Lanes at the Glenmont Arcade, was owned by Rinaldi Enterprises and suggests a reason for the selection of the firm to design the Glenmont bowling alley. The Silver Spring Presbyterian Church was constructed in 1959, but by the completion of the Glenmont Arcade in late 1960, the firm’s partnership had ended.

Bartley opened a new firm with Warren D. Davis in Wheaton, designing commercial and institutional buildings such as the Berkeley Plaza Shopping Center (1965) in Martinsburg, West Virginia and Flower Valley Elementary School (1968) in Rockville, Maryland. In 1971, Davis left the partnership, starting his own architecture, planning, and engineering firm; Bartley continued to practice alone into the 1980s. Gates worked solo for a time in the 1960s, winning awards for houses designed for the Steven Kokes, Inc. development company in 1960 and 1964. In the early 1980s, he opened the firm of Boekl-Gates and was a partner until his death in 1994. The firm continues to exist today, specializing in architecture and interior design.

Owners/Developers:

The shopping center has a complex history of development. While it is clear that there was a single developer, H. Glenn Garvin, who sought to create a local shopping center on a tract of former farmland, it appears that most stores in the Glenmont Shopping Center were owned individually or in small groups rather than by a single-entity company that managed the entire shopping center. Land plats from the 1958-59 development of the parcels and current land records support the evidence that the land was divided into four pieces: the Grand Union Supermarket, the Peoples Drug Store, the Glenmont Arcade, and the group of stores in between the Peoples Drug Store and the Glenmont Arcade. (figs. 1-3) The original owners of this last segment of stores were August and Ludwig Heller, two brothers who emigrated from Germany and opened a bakery in Chevy Chase in 1928. Their business expanded over the years and it appears that they purchased the land in Glenmont as an investment; it is believed that their descendents continue to act as proprietors of the stores.

H. Glenn Garvin (developer)

H. Glenn Garvin (1922-1991) was born in Wheeling, West Virginia and was raised in Silver Spring, Maryland. A real estate agent and developer of commercial properties in Washington, D.C. and its suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s, he developed the Glenmont Shopping Center through various companies, including the Glenmont Investors’ Syndicate, the Glenmont Land and Development Corporation, and Glenn-Ernie.

Garvin’s interest in the Wheaton-Glenmont area began as early as 1952, when he applied for and was denied a permit to build a cemetery approximately two miles north of the shopping center site in Glenmont. Garvin began working with smaller commercial ventures including the 1954 leasing of a small group of five stores and offices in Wheaton. Within two years, his interest shifted towards large-scale residential developments outside of the Washington, D.C. area. In 1956, Garvin’s office acted as the leasing agent for the opening of Corolla, North Carolina, a $25 million resort city on the Outer Banks; in 1957, the Garvin office was the exclusive sales agent for the purchase of 110 lots in the Manor Club Estates development of Olney, Maryland. In 1965, Garvin moved to Boca Raton, Florida and lived there until his death in 1991.

Make it stand out.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.

Grand Union

Square Deal Market, which purchased the parcel of the shopping center closest to Georgia Avenue in 1958, was a local supermarket chain with fourteen stores in the Washington, D.C. area by 1954. The following year, the company was acquired by Grand Union, a supermarket corporation based in New Jersey with markets along the Eastern Seaboard. In January 1959, Grand Union announced the opening of a supermarket on their recently purchased land at the intersection of Georgia Avenue and Layhill Road. The supermarket was described as providing 30,000 square feet of retail space and parking for 335 cars; the use of a truss roof would eliminate approximately 80 percent of columns typically found in supermarkets. The construction was possible because of a $350,000 loan from a New York investment company, the Sonnenblick-Goldman Corp. In January 1959, the Grand Union in Glenmont was one of four Grand Union supermarkets that had opened in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area within the previous four months; the other three opened in Arlington and Alexandria, Virginia. By 1960, there were more than ten Grand Union supermarkets in Montgomery County alone.

That same year, all Square Deal and Food Fair markets in the DC area changed their names to Grand Union. Despite financial problems in the 1970s, a change in upper management brought in profits in the 1980s and led to the selling of the chain in 1989 to an investment banker. The company continued to struggle with profits, filing for bankruptcy in 1995 and again in 1998 and closing or remodeling many of its older stores; by 2001 it was acquired by one of its largest creditors, C&S Wholesale Grocers. Grand Union’s remaining twenty-one stores were purchased in 2012 by Tops Markets, and several stores changed their name to Tops Friendly Markets.

The Peoples Drug Store

The Peoples Drug Store, another local business chain, purchased the strip of land adjacent to the supermarket’s parcel in 1958. The first Peoples Drug Store opened in Washington, D.C. in 1905 at 824 7th Street, Northwest. After encountering success in offering merchandise in addition to the typical prescriptions and medications, the store quickly expanded with the growing population of Washington, D.C. during the first quarter of the twentieth century, particularly after installing soda fountains in stores beginning in 1925. By 1929 the Peoples Drug Store was operating 98 stores in Washington, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. By 1955, the number had grown to 156 stores, with plans to open another 27 new stores by 1957. The company continued to expand throughout the 1970s until it was purchased in 1975 by Lane Drug of Toledo, Ohio and then subsequently in 1984 and 1990 by Imasco and CVS, respectively.

At the time of its opening in March 1959, the Peoples Drug Store in Glenmont was the largest self-service unit that the company had ever opened. Two other stores had recently opened nearby in Montgomery County, and three more were reported to open in the subsequent three months.

Rinaldi Enterprises & Tuffy Leemans

Rinaldi Enterprises, original owners of Glenmont Lanes and possibly the entire Glenmont Arcade, was founded by LeRoy Rinaldi and his brother, Nicholas, a well-known local bowler. Nicholas had won several local competitions in the 1930s and 1940s, including the 1933 Italian Sweepstakes and a 1941 special Clarendon match. In the late 1950s, the brothers opened Wheaton Bowling and Recreational Center (later called Wheaton Triangle Lanes), expanding their bowling company over the next few years to include several other local bowling alleys in Glenmont and Hyattsville, Maryland. In 1960, however, after a series of disagreements, the two agreed to separate their interests in the company, with Nicholas maintaining ownership of the new Glenmont Lanes and LeRoy of Wheaton Bowl and Queenstown Duck Pin Bowl.

After the splitting of the company, Nicholas Rinaldi sold half of his share of Glenmont Lanes to Alphonse E. Leemans (1912-1979), a former football player for the New York Giants. “Tuffy,” as he was known, was a college football player for George Washington University until 1936, when he was spotted and drafted second for the Giants in the National Football League’s first-ever college draft. Leemans continued to play for the Giants until 1943, when he was forced to retire because of injuries from the 1942 season. He returned to the Washington, D.C. area in 1953, coaching football for a local high school for several years. In 1959, he was inducted into the Football Hall of Fame. At some point in the 1960s, Rinaldi sold his remaining half of the ownership to Leemans, preferring to own and manage other bowling establishments in the area. In the 1970s and 1980s, Rinaldi purchased and managed eleven other bowling alleys in Montgomery County and the Miami-Fort Lauderdale area of Florida in the 1970s.

Glenmont Lanes, however, stayed under Leemans’ proprietorship until his death in 1979, even changing the name of the establishment to “Tuffy Leemans’ Duckpin Bowling Alley.” His daughter, Diane Kelly, then took over ownership until the closing of the alley in 2002.

Original and subsequent occupants:

Since its opening, occupants of the Glenmont Shopping Center have been constantly in flux; this trend continues into the present and reflects market changes of the nearby community. Basic amenities, including a barber, hair salon, dry cleaners, grocery store or supermarket, and drug store have been located at the shopping center since its opening, but the owners and locations of these stores have changed over the years. Other secondary, more specific services and stores come and go depending on local needs and availability.

1959:

Grand Union Supermarket

People’s Drug Store

1960-1962:

Barber

Dry Cleaners

Glenmont Lanes (also called Glenmont Alleys)

Glenmont Electric Appliance Service Engineers

Hair stylist

Hi-Gear Discount Tire & Auto Center

Meenehan’s Hardware Store

National Plate Glass and Mirror Company

New Buddha Chinese Restaurant

Pitrone’s Book and Records

Telco Television Store

another restaurant

and other small businesses

1972:

A&T Office Machines

Arcade Florists

Arcade Card & Gift Shop

Citizens Bank

Glenmont Arcade Sewing Center

Glenmont Barber Shop

Glenmont Cleaners

Glenmont Inn Bar

Grand Union

Hair Stylists

High’s

Hi-Gear Discount Tire & Auto Center

King of China Hall

Mary Carter Paints

Meenehan's Hardware

New Buddha Restaurant

Peoples Drug Store

Tuffy Leemans’ Glenmont Lanes

Virginia Lippy Dance Studio

Current Occupants (2013):

Arcade Florist

Check Cashing

CVS

D’anna Dance Center

Glenmont Martial Arts Academy

Grocery Store

Glenmont Cleaners

Hair Cuttery

Iglesia de Cristo Mi-El

Mayflower Buffet

OK Barber Shop

Pearls Nail & Spa

Sports World

Staples

Szechuan Place (now vacant)

Tax Guru

Original plans and construction:

Site

The Glenmont Shopping Center sits on a tract of land at the intersection of Randolph (formerly Old Annapolis Road), Georgia Avenue (previously Washington and Brookeville Turnpike), and the road today known as Layhill Road. Beginning sometime prior to 1865, the property was owned by William C. Pierce; by 1879, the intersection was the site of “many fine farms and elegant residences” and a local country store run by S.H. Jones. Wheaton, the small village approximately a mile and a half south along Georgia Avenue, was home to one postmaster, a blacksmith, six merchants, a physician, and thirty-nine farmers. The 242 acre Pierce tract remained intact and in the family until sometime around the turn of the century, when the farm was sold to William F. Garber. By the early twentieth century, the parcel of land located on the northwestern corner of the Layhill Road and Georgia Avenue intersection (just west of the Garber parcel) had been subdivided into small farming tracts and a roadhouse that was later converted into a grocery store called Xander’s Market during the Prohibition Era. The Garber farm, however, remained unsubdivided into the 1950s.

Like much of Montgomery County, Glenmont retained its rural character into World War II despite the creation of several small subdivisions near the Garber tract in the late 1930s. More subdivisions, including Glenmont Forest, Glenmont Village, and Glenmont Hills were platted and developed between 1947 and 1950, all located south and west of the shopping center site. As the population of the area increased, sewer lines were laid down and roads widened to accommodate traffic and further population growth. In 1952, Georgia Avenue was widened to a two-lane roadway, extending from Colesville Road up to Glenmont. Shortly thereafter, a group of four business men – Edward C. Baltz, president of the Perpetual Building Association; Thornton W. Owen, past president of the Washington Board of Trade; David S. Moore, an investment broker and developer; and Edward L. Strohecker, Sr., a real estate operator – together purchased the Garber tract as well as the piece of land directly to the south on the other side of Randolph Avenue. The smaller parcel on the south side of Randolph Avenue was quickly sold to the Kensington Volunteer Fire Department, which erected a firehouse in October 1953. At the time of its construction, the firehouse was the first public service building in the area.

The future site of the Glenmont Shopping Center, however, remained undeveloped for another five years despite initial plans for one thousand new houses and a shopping center on the parcel. Plans to authorize bonds to extend the Northwest Branch sewer line to the area were announced almost immediately after the property purchase, but it appears that utilities were not brought to the area until the development of the Glenmont Knolls subdivision, located north of the shopping center site, in 1958 and 1959.

The initial 1952 development plans for the site were perhaps premature; most of the post-World War II development in Montgomery County was focused on the southern portion of the county, centering on the Silver Spring and Bethesda/Chevy Chase area. It was not until the late 1950s and into the 1960s that residential centers began to shift northward toward Wheaton and Rockville. With this shift in population growth and a convenient location at the locus of two major roads in the area, financing was granted for the first retailer at the Glenmont Shopping Center, Square Deal Market (soon to be called Grand Union), and further development plans followed suit.

Building – Disjointed Development

The first completed store of the Glenmont Shopping Center was the 30,000 square-foot Grand Union supermarket. Constructed of red brick laid up in American bond with a glazed façade and large glass entrance, a truss ceiling to minimize the number of steel columns, and a shallow white arched roof, the building was located on the western side of the lot. Only two months afterward, the Peoples Drug Store opened its 15,000 square-foot store in the lot east of the supermarket. Large plate glass windows ran across nearly the entire storefront, held in place with slim metal framing members with a single decorative line of beading in the middle. The entrance, located on the western side of the store, was recessed several feet into the retail space, and the display windows on either side angled inwards to accommodate this. Red brick, also laid up in American bond, framed the display windows on either side of the storefront, and several courses of red Roman brick were used underneath the windows to create a base to the storefront. Unlike the Grand Union supermarket next door, the Peoples Drug Store had a flat roof. A flat canopy ran over the sidewalk in front of both stores.

In 1960, the shopping center expanded with a single shop in the leftover space on the west side of the Grand Union and five stores and the Glenmont Arcade on the east side of the Peoples Drug Store. Each of these storefronts had a single front entrance flanked by large plate glass display windows with an American bond brick base reaching from the bottom of the windows down to the sidewalk. The entire band of stores was covered with a flat roof and canopy that extended over the sidewalk and was held up with round steel columns. A parapet, also of brick, extended upward above the flat canopy.

The largest portion of the 1960 section was the Glenmont Arcade and Bowling Alley, with large yellow, black, red, and bright blue neon “Glenmont Arcade” and “Bowling” signs over the entranceway. The Arcade, a wide, covered pedestrian corridor with small shops on either side, terminated in a stairway leading down to the bowling alley in the basement of the building (fig. 4). The shops in the arcade were approximately fifteen feet wide and intended for small, one-person businesses; their plate glass and aluminum framed storefronts angled into the walkway at forty-five degrees so that individual storefronts could be visible from the entrance to the arcade. It is likely that the architects selected the arcade as a typology because of its ease in accommodating the local need for smaller businesses in one area and its desired emphasis on a final destination – a stairway leading down to the bowling alley. Glenmont Lanes had twenty-four lanes and a snack bar. Four other shops, one on the east side of the entrance to the passageway and three on the western side, were constructed at the same time; each also had large plate glass storefronts with brick surrounds.

The rest of the shopping center parcel – the southern part of the lot closest to the Randolph Road-Georgia Avenue intersection – was left for use as parking for several hundred cars. Behind the shopping center was a service alleyway for deliveries and garbage disposal.

Alterations and additions:

In the 1970s and 1980s, several changes were made to the shopping center. Two additions, one adjacent to the Glenmont Arcade portion on the eastern side and the other a longer section that ran perpendicular and southwards from the existing stores, were added sometime in the 1980s.

In the 1970s, the Grand Union chain closed its stores in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan region and the store became a Magruders Supermarket and later a Staples office supply store. As a result, changes to the exterior of the store, including its main entrance and roof, have been altered. The barrel vault of the original supermarket was concealed behind a mansard roof-type façade addition and currently by large signage. The Peoples Drug Store was acquired by CVS in the 1990s and replaced the original entrance with a more contemporary one with automatic doors and smaller panes of glass. The parapet has been covered with a neoclassical-inspired parapet and the store’s name. The group of stores adjacent to the Arcade on the west side have also changed the parapet, extending its width to the end of the canopy, adding store signage, and topping this wide new parapet with an orange-red gable roof that matches several parapets of the later perpendicular extension. Several of these storefronts have also been modified, and the circular steel poles supporting the overhead canopy have been squared off and covered with beige brick masonry.

Several of the plate glass windows within the Glenmont Arcade have been replaced and new framing members have been added. The interior of the basement of the arcade has been converted from a bowling alley to a church, removing most of the architectural elements including the alleys, seats, and machinery.

Historical Context

Post-WWII Shopping Centers in the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area

Access to commercial retail has been a consideration in planned suburban communities since the 1920s. While some of the earlier upscale communities in Montgomery County at the turn of the century such as Chevy Chase banned commercial facilities from their developments, the planners of Battery Park (1923), Leland (1924), and Montgomery Hill (1928) made specific provisions for a small commercial zone in their plans. To obscure their commercial nature, these centers often employed historicist architectural styles similar to their residential neighbors.

Beginning in the 1930s, larger and more local shopping centers emerged in Washington, D.C. and its outlying areas. The opening of Park and Shop in Cleveland Park in 1930 spurred the creation of several “one-stop” shopping centers throughout the metropolitan area, usually to serve either an existing community or as part of a newly developed one. Simultaneously, several blocks along Georgia Avenue in Silver Spring had emerged as a local commercial downtown, a “Main Street,” for new communities in Montgomery County that did not include plans for a neighborhood shopping center; by 1935, the strip of stores was described as "fast-growing" and "modern." While news articles and advertisements for new residential developments often included information on nearby shopping facilities, these early shopping centers of fewer than fifteen stores were convenient and easy to reach but were intended as a complement, not a replacement, to the downtown Washington, D.C. shopping experience.

It was not until the post-war era that shopping centers of a much larger scale emerged in competition with downtown. Although there were several examples of shopping centers from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s that counted more than 50 stores in one grouping, including the pioneering Country Club Plaza (1922, Edward Buehler Delk and later Edward W. Tanner, architects) in Kansas City, Missouri, these facilities were very rare. This was in part due to the struggling economy of the Great Depression and also due to the time, effort, and risk associated with developing a shopping center compared to a residential development, where one could turn a quick, easy profit in under a year. A shopping center, on the other hand, required careful planning from the initial surveying and purchasing of the land to the selection of tenants and maintenance of the facilities; coordination could take years. However, early worries about the profitability of shopping centers in suburban areas were laid to rest in the late 1940s as owners continued to profit and centers grew with the postwar economy and population boom.

Indeed, shopping centers experienced unprecedented growth during the 1950s. In the early 1950s, thirty to fifty shopping centers opened nationally each year, catering largely to new suburban developments with relatively small, convenient facilities. Glenmont Arcade and Shopping Center, for example, opened several years after the platting of nearby subdivisions in the 1950s. Although five shopping centers opened between 1950 and 1959 in the Wheaton-Glenmont area, including Wheaton Plaza, with over sixty stores, the growing population of the area was able to support further commercial development. There seemed to be no end to the creation of shopping centers in the area and across the country. Scholars have attributed this nation-wide trend to multiple factors, including tax breaks on commercial properties that made shopping center developments particularly lucrative, population increases, racial tensions in urban environments and “white flight,” the growth of suburbs, increased car ownership, and higher incomes in the post-war economy.

Of these reasons, rising incomes played a particularly significant role in the increased spending of the 1950s. Incomes rose dramatically from $576 per person in 1940 to $1,708 per person in 1955. Much of this income was spent on items that were rationed or not in production during the wartime economy, such as cars, or on items that were unable to be purchased during the Depression because of price. Other objects simply had not existed before the war but could be afforded by the average middle-class family because of new technology and relatively inexpensive materials like plastic. The home and everything associated with it became the epicenter of the “American Dream” and “symbolized… a brave new world of worldly goods.” Shopping and the purchasing of these “worldly goods” became a way to overcome the era’s frustrations with the sacrifice of the Great Depression and the Second World War and express middle-class comfort, and advertisements and the media further encouraged this consumption. If the home became the place to display middle-class identity through objects and goods, then the shopping center – the place where these objects could be purchased – became the locus of consumer culture and thus proliferated.

Also significant in the success of shopping centers was their appearance and the addition of new programmatic uses. The inclusion of greenery, benches, places for children to play, and sporting and entertainment facilities such as movie theaters and bowling alleys together portrayed the shopping center as a place of pleasure and leisure. What was once a chore was instead marketed as a recreational activity, with entertainment for the whole family. Unified architectural elements instead of haphazard planning and signage, possible through single-entity ownership, continued the domestication of the retail facility and emphasized enjoyment, ease, and relaxation. The inclusion of a bowling alley in the basement of the Glenmont Arcade, for example, made the Glenmont Shopping Center more than the one-stop shopping center of the Park and Shop era; it was a one-stop park, shop, eat, and play center.

Classy or “Trashy:” Shopping in Montgomery County, 1930-1970

In the early days of Montgomery County’s transformation from rural farmland to developed suburbia, shopping beyond one’s basic necessities occurred in downtown Washington, D.C. This was partially due to the lingering Victorian desire to maintain property values through the separation of commercial and industrial zones – seen as belonging to the lower classes – from residential areas, and partially due to the relatively small population of the county until the 1930s. Early shopping centers both large and small sought to camouflage their overtly commercial nature through the use of historical styles, but by the 1930s the small, local shopping center was considered beneficial to new residential communities outside of Washington, D.C. because of convenience and changes in the socio-economic class of newcomers to Montgomery County.

Many of the earlier residences of the down-county area were large summer houses to some of Washington, D.C.’s wealthier citizens, and shopping for household goods was a task completed by servants. Although the wealthy enjoyed the experience of shopping in the elegant and exclusive department and clothing stores in the downtown retail district, shopping involving food and other daily necessities – “marketing” – was relegated to servants. These items were typically shipped from downtown up to Montgomery County via railway or streetcar lines, where servants would pick them up from the nearest railroad or streetcar stop. However, most of the new residents in the county in the 1920s and 1930s were middle-class workers employed through the expanding federal government of the Roosevelt administration and could rarely afford servants. Nearby, convenient shopping with the basic amenities of a supermarket and drug store became acceptable, if not necessary.

An early attempt at mediating between the desire to reside in a commercial-free area and the realities of middle-class living was located in the formerly commercial-free Chevy Chase, Maryland at the Chevy Chase Arcade (1925, Louis R. Moss, architect) on Connecticut Avenue. Historically, the arcade – a covered pedestrian walkway surrounded by retail storefronts – emerged as a commercial building type originating in Paris in the late eighteenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century, it had become a common commercial prototype for the upper- and middle-class, combining access to luxury goods with the opportunity to promenade and be seen. The arcade was subsequently introduced to over thirty countries, and the first known arcade in the United States in Providence, Rhode Island (1827) led to the construction of several similar historically-inspired arcades in Philadelphia and New York prior to the Civil War. By the 1910s and 1920s, however, the arcade had fallen out of favor despite the convenience of its covered walkways and the allure of its highly decorated interiors. Urban environments shifted towards the use of more obvious and attention-drawing storefronts that opened to the street, but the 1925 construction of the Chevy Chase Arcade marked an unusual but significant example of the building type in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. Its emphasis on interior commercial spaces and classically-inspired facade provided a tamer, more unified storefront in the wealthy Chevy Chase community compared to the disorganized and disjointed storefronts elsewhere in the county and was deemed a “beautiful and costly building” by The Chevy Chase News. Despite the initial success of the Chevy Chase Arcade, the arcade as a commercial prototype was rarely imitated in later years.

It was not until the 1938 opening of the Silver Spring Shopping Center (John Eberson, architect) that a long-lasting, locally influential solution to the “haphazard placement” of storefronts along Silver Spring’s Georgia Avenue was found. Despite the acknowledged convenience and purported “progressiveness” of downtown Silver Spring, its lack of unification meant that it was simultaneously seen as detrimental to the county’s scenic beauty and concepts of middle-class cleanliness. The Silver Spring Shopping Center, however, was “a thoroughly studied plan for a great business center” and allowed for enduring unified design because of single-entity ownership that leased, managed, and maintained the center. Its nineteen stores including a grocery store, drug store, clothing shops, and movie theater were sheathed in light-colored Bedford stone and a dark polished granite base; long bands of granite and glazed brick following the building’s flat roof emphasized its horizontality, and curved corners alluded to the aerodynamic Streamline Moderne style of automobiles, trains, and airplanes. Woodmoor Shopping Center (1939, 1948, 1954, Schreier & Patterson, architects), located three miles north of the Silver Spring Shopping Center, was one of several others throughout the D.C. metropolitan region that continued the use of Streamline Moderne as a way to present a cohesive, socially acceptable commercial venture. These unifying features and the opportunity to shop, eat, and be entertained all within one complex made the Silver Spring Shopping Center the preferred retail experience in Montgomery County.

Few, if any, shopping centers were constructed in Montgomery County during World War II; by the end of the 1940s, however, the Silver Spring Shopping Center’s model of single-entity ownership was replicated throughout the county as local shopping centers appeared along major travel routes. By the 1950s, shopping centers were no longer simply small local groups of stores, and three distinct types of centers emerged: the small, local “community center,” the semi-regional center, and the large regional center. Regardless of size, the term “shopping center” implied a sense of “glamour” and prestige and marked the retail center as distinct from “almost any group of stores strung together… in a strip or cluster.”

Along with the “glamour,” however, came protests from residents who saw any form of commercial development in their immediate neighborhood as undesirable. Although the Montgomery County Planning Department first began developing zoning regulations in 1949 and master plans for individual villages and towns shortly thereafter, countless Montgomery County Council meetings in the 1950s and 1960s were devoted to deliberations and discussions of alterations to earlier zoning decisions. Some underdeveloped areas, particularly those in northern and western parts of the county such as Cabin John, were urged to rezone land for commercial use to benefit from increased land values and profits from retail stores. Other towns, on the other hand, struggled to combat further commercial development, citing traffic, a threat to current residential character, oversaturation of the local retail market, and a possible depreciation in property values as reasons for opposition.

In the Wheaton-Glenmont area, shopping centers became a topic of concern in the mid-1950s when approval was obtained for the construction of Wheaton Plaza, a regional shopping center with over sixty stores and 5000 parking spaces. Early beliefs that a large regional shopping center in Wheaton would “affect the morals, safety, health and welfare of the residents” eventually gave way to the accepting of Wheaton Plaza and other shopping centers as an economic boon to the area. More importantly, however, the shopping center was deemed acceptable and even desirable by the community because of its single-entity ownership that allowed for unified, careful planning of its interior and exterior spaces to create a “tranquil” and pleasant shopping experience. A large decorative marble fountain, marble and stone tile flooring, shrubbery, exotic wood floors, Florentine glass mosaic panels, bubbles, globes, and hemispheres and “tranquil pastel colors” drew in customers and offered an aesthetically pleasing, relaxing, fashionable atmosphere. The interior of the Woodward & Lothrop store, a major area department store, was designed with stylish modern finishes but with the intention “to make it as homey as the old country store with a pot-bellied stove in the middle of it.” These seemingly innocuous design choices, along with the “Georgetown-style white-trimmed red brick” of the exterior attempted to recreate select parts of a domestic environment so that the largely female shopping population would find the shopping center appealing and comforting yet still elegant and up-to-date. The overall vision of the large-scale, carefully planned and designed shopping center was necessarily one of modernity, progress, and leisure.

Smaller shopping centers, however convenient and useful they may have been, were quickly deemed inferior to the larger regional centers. Their undistinguished presence often required the use of neon lights and automobile-oriented architecture, sometimes in the futuristic “Googie” style, a popular form of commercial design in the late 1950s and 1960s dominated by bright colors, irregular shapes, and exaggerated forms. Residence in Montgomery County in the late 1960s would most likely require living “next to a monolithic high-rise apartment, or even a neon-lighted shopping center…” deplored one author. Uncoordinated signage in particular was seen as unacceptable, and in 1965 the Montgomery County Council created a twenty-member Committee for a More Beautiful Montgomery County to develop programs to address landscaping and signage throughout the county. The program was likely inspired by First Lady Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson’s creation of the Committee for a More Beautiful Capital, but the Montgomery Committee had no enforcement powers or authority regarding zoning matters. However, it staged a “beautification rally” in the parking lot of Wheaton Plaza in October 1965 and conducted a tour of Montgomery County’s shopping centers in 1966, specifically citing the Glenmont Shopping Center as “trashy in appearance” with “promiscuously placed signs” and “no design value;” moreover, the shopping center was surrounding by “an eyesore” of a parking lot. Different ownership of each area or store of the shopping center meant that there were little, if any, signage or storefront guidelines for each shop to follow, resulting in a plethora of competing advertisements, signs, and storefronts; the effect was reminiscent of the unpleasant, haphazard strip of disjointed stores along Georgia Avenue in Silver Spring in the 1930s. Even the Glenmont Arcade’s emphasis on uniform storefronts and an inward-focused commercial space was not seen as an exemplary retail environment as the earlier Chevy Chase Arcade had. Instead, the Arcade in combination with its surrounding stores was seen as suburban blight compared to the nearby marble-floored, pastel-painted Wheaton Plaza. The Glenmont Shopping Center was the antithesis of the ideal shopping experience.

This negative view of the shopping center has persisted into the present as plans for redevelopment of the area immediately surrounding the 1998 metro station have moved forward. The January 2012 Glenmont Sector Plan, written by the Montgomery County Planning Department, described the shopping center as having “a poor vehicle circulation pattern, inadequate pedestrian facilities, and a low aesthetic value.” While the plan cites hopes of redeveloping the shopping center and perhaps retaining portions of the Glenmont Arcade and Shopping Center, this could prove difficult given the thirteen different owners of different portions of the shopping center. Several local residents, including Kris Kumaroo, the founder and former president of the Greater Glenmont Civil Association, feel that the shopping center lacks architectural merit and should be completely redeveloped; owners and developers should “start it over.”

“Googie” and “Exaggerated Modern” Architecture

While the earliest shopping centers of the 1920s relied on historicist styles to mask the commercial nature of their shops and the shopping centers of the 1930s and 1940s often employed the graphic, automobile-oriented banding and curved corners of Streamline Moderne, by the 1950s, the shopping center itself no longer needed to function aesthetically as a local landmark. Shopping center design shifted toward utility as economic studies declared design flourishes as superfluous and of little aid in increasing profits. It remained important to focus on uniformity and landscaping throughout the plaza to maintain a comfortable, domestic feel, but advertising and signage, particularly near or beyond large parking lots, became increasingly important. While the Glenmont Shopping Center provided little in the way of uniformity or landscaping, the brightly colored, “Googie” neon sign over the arcade portion of the center spoke to a desire to move beyond the bare basics of signage and attract the passing motorist.

“Googie” architecture, or “exaggerated modern” as it is sometimes known, originated in suburban California in the 1950s and 1960s as an answer to the problems of automobile-oriented architecture and out of changing aesthetics of the late 1950s. Characterized by large, colorful, irregularly-shaped signage, unusual roof forms, and the influence of space-age technology, the style was critiqued by many because of its overtly commercial nature and its “corrupted versions of high-art designs.” The over-the-top, euphoric style mimicked the era’s exuberance of consumption as new technologies and products became within reach of middle-class spending. Just as objects that had previously been seen as luxuries turned into necessities, so too did the design of products, shifting from streamlined, efficient styles design to the lavish, almost gaudy colors and materials of “exaggerated modern.”

Although signage had long played an important role in commercial architecture, the irregular forms, bright colors, and exaggerated shapes were neither classically- nor traditionally-inspired, nor did they follow Modernism’s main tenet of the avoidance of applied ornament. Critics were unsure of how to classify the “exaggerated modernism” of coffee shops and drive-in restaurants, or if they were even worthy of being examined at all. However, “Googie” architecture was inspired by genuine optimism and a belief in technical progress and the future. Forms were meant to appear as though they defied gravity entirely, like the airplanes and spacecrafts of the postwar era. Architectural critic Douglas Haskell wrote an article for House and Home in 1952 about the style, describing elements that appeared to “hang from the sky;” it was, he declared, “an architecture up in the air.”

The style was further influenced by two international exhibitions, the Seattle Century 21 Exposition (1962), with Seattle’s Space Needle representing the zenith of human abilities, and the New York World’s Fair’s (1964) Unisphere, Space Park, and General Motors “Futurama II” exhibit. The General Motors pavilion in particular evoked the ethereal abilities of architecture and technology, greeting its visitors with a huge, sweeping entrance building whose curved form and hovering canopy resembled an airplane wing. The international fairs, while celebrating the futuristic “Googie” style, simultaneously marked the beginning of its demise as people began to view its shapes and implied modernity as empty and naïve. The American dream of living in suburbs and owning a car, the epitome of middle-class comfort, had already been achieved, and the realities of race and gender inequality had been brought to the forefront of American culture.

The simple canopy of the Glenmont Shopping Center, while not as architecturally sophisticated as the designs of the international exhibitions, intended to produce the illusion of floating signage and roofs through cantilevers and small metal piers. The canopy above the arcade portion of the shopping center is even more dramatic than that of the surrounding stores, protruding out further and higher. The signage above also suggests a playfulness and lightness through a mixing of color choices (canary yellow, bright blue, and red contrast with a black background) and floating diamonds and rectangles. Easily visible from several hundred feet away, it is perhaps this signage, along with that of the rest of the shopping center, which caused the members of the Committee for a More Beautiful Montgomery County to refer to the Glenmont Shopping Center as “flashy” and “trashy.”

Classy or “Trashy:” Shopping in Montgomery County, 1930-1970

In the early days of Montgomery County’s transformation from rural farmland to developed suburbia, shopping beyond one’s basic necessities occurred in downtown Washington, D.C. This was partially due to the lingering Victorian desire to maintain property values through the separation of commercial and industrial zones – seen as belonging to the lower classes – from residential areas, and partially due to the relatively small population of the county until the 1930s. Early shopping centers both large and small sought to camouflage their overtly commercial nature through the use of historical styles, but by the 1930s the small, local shopping center was considered beneficial to new residential communities outside of Washington, D.C. because of convenience and changes in the socio-economic class of newcomers to Montgomery County.

Many of the earlier residences of the down-county area were large summer houses to some of Washington, D.C.’s wealthier citizens, and shopping for household goods was a task completed by servants. Although the wealthy enjoyed the experience of shopping in the elegant and exclusive department and clothing stores in the downtown retail district, shopping involving food and other daily necessities – “marketing” – was relegated to servants. These items were typically shipped from downtown up to Montgomery County via railway or streetcar lines, where servants would pick them up from the nearest railroad or streetcar stop. However, most of the new residents in the county in the 1920s and 1930s were middle-class workers employed through the expanding federal government of the Roosevelt administration and could rarely afford servants. Nearby, convenient shopping with the basic amenities of a supermarket and drug store became acceptable, if not necessary.

An early attempt at mediating between the desire to reside in a commercial-free area and the realities of middle-class living was located in the formerly commercial-free Chevy Chase, Maryland at the Chevy Chase Arcade (1925, Louis R. Moss, architect) on Connecticut Avenue. Historically, the arcade – a covered pedestrian walkway surrounded by retail storefronts – emerged as a commercial building type originating in Paris in the late eighteenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century, it had become a common commercial prototype for the upper- and middle-class, combining access to luxury goods with the opportunity to promenade and be seen. The arcade was subsequently introduced to over thirty countries, and the first known arcade in the United States in Providence, Rhode Island (1827) led to the construction of several similar historically-inspired arcades in Philadelphia and New York prior to the Civil War. By the 1910s and 1920s, however, the arcade had fallen out of favor despite the convenience of its covered walkways and the allure of its highly decorated interiors. Urban environments shifted towards the use of more obvious and attention-drawing storefronts that opened to the street, but the 1925 construction of the Chevy Chase Arcade marked an unusual but significant example of the building type in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. Its emphasis on interior commercial spaces and classically-inspired facade provided a tamer, more unified storefront in the wealthy Chevy Chase community compared to the disorganized and disjointed storefronts elsewhere in the county and was deemed a “beautiful and costly building” by The Chevy Chase News. Despite the initial success of the Chevy Chase Arcade, the arcade as a commercial prototype was rarely imitated in later years.

It was not until the 1938 opening of the Silver Spring Shopping Center (John Eberson, architect) that a long-lasting, locally influential solution to the “haphazard placement” of storefronts along Silver Spring’s Georgia Avenue was found. Despite the acknowledged convenience and purported “progressiveness” of downtown Silver Spring, its lack of unification meant that it was simultaneously seen as detrimental to the county’s scenic beauty and concepts of middle-class cleanliness. The Silver Spring Shopping Center, however, was “a thoroughly studied plan for a great business center” and allowed for enduring unified design because of single-entity ownership that leased, managed, and maintained the center. Its nineteen stores including a grocery store, drug store, clothing shops, and movie theater were sheathed in light-colored Bedford stone and a dark polished granite base; long bands of granite and glazed brick following the building’s flat roof emphasized its horizontality, and curved corners alluded to the aerodynamic Streamline Moderne style of automobiles, trains, and airplanes. Woodmoor Shopping Center (1939, 1948, 1954, Schreier & Patterson, architects), located three miles north of the Silver Spring Shopping Center, was one of several others throughout the D.C. metropolitan region that continued the use of Streamline Moderne as a way to present a cohesive, socially acceptable commercial venture. These unifying features and the opportunity to shop, eat, and be entertained all within one complex made the Silver Spring Shopping Center the preferred retail experience in Montgomery County.

Few, if any, shopping centers were constructed in Montgomery County during World War II; by the end of the 1940s, however, the Silver Spring Shopping Center’s model of single-entity ownership was replicated throughout the county as local shopping centers appeared along major travel routes. By the 1950s, shopping centers were no longer simply small local groups of stores, and three distinct types of centers emerged: the small, local “community center,” the semi-regional center, and the large regional center. Regardless of size, the term “shopping center” implied a sense of “glamour” and prestige and marked the retail center as distinct from “almost any group of stores strung together… in a strip or cluster.”

Along with the “glamour,” however, came protests from residents who saw any form of commercial development in their immediate neighborhood as undesirable. Although the Montgomery County Planning Department first began developing zoning regulations in 1949 and master plans for individual villages and towns shortly thereafter, countless Montgomery County Council meetings in the 1950s and 1960s were devoted to deliberations and discussions of alterations to earlier zoning decisions. Some underdeveloped areas, particularly those in northern and western parts of the county such as Cabin John, were urged to rezone land for commercial use to benefit from increased land values and profits from retail stores. Other towns, on the other hand, struggled to combat further commercial development, citing traffic, a threat to current residential character, oversaturation of the local retail market, and a possible depreciation in property values as reasons for opposition.

In the Wheaton-Glenmont area, shopping centers became a topic of concern in the mid-1950s when approval was obtained for the construction of Wheaton Plaza, a regional shopping center with over sixty stores and 5000 parking spaces. Early beliefs that a large regional shopping center in Wheaton would “affect the morals, safety, health and welfare of the residents” eventually gave way to the accepting of Wheaton Plaza and other shopping centers as an economic boon to the area. More importantly, however, the shopping center was deemed acceptable and even desirable by the community because of its single-entity ownership that allowed for unified, careful planning of its interior and exterior spaces to create a “tranquil” and pleasant shopping experience. A large decorative marble fountain, marble and stone tile flooring, shrubbery, exotic wood floors, Florentine glass mosaic panels, bubbles, globes, and hemispheres and “tranquil pastel colors” drew in customers and offered an aesthetically pleasing, relaxing, fashionable atmosphere. The interior of the Woodward & Lothrop store, a major area department store, was designed with stylish modern finishes but with the intention “to make it as homey as the old country store with a pot-bellied stove in the middle of it.” These seemingly innocuous design choices, along with the “Georgetown-style white-trimmed red brick” of the exterior attempted to recreate select parts of a domestic environment so that the largely female shopping population would find the shopping center appealing and comforting yet still elegant and up-to-date. The overall vision of the large-scale, carefully planned and designed shopping center was necessarily one of modernity, progress, and leisure.

Smaller shopping centers, however convenient and useful they may have been, were quickly deemed inferior to the larger regional centers. Their undistinguished presence often required the use of neon lights and automobile-oriented architecture, sometimes in the futuristic “Googie” style, a popular form of commercial design in the late 1950s and 1960s dominated by bright colors, irregular shapes, and exaggerated forms. Residence in Montgomery County in the late 1960s would most likely require living “next to a monolithic high-rise apartment, or even a neon-lighted shopping center…” deplored one author. Uncoordinated signage in particular was seen as unacceptable, and in 1965 the Montgomery County Council created a twenty-member Committee for a More Beautiful Montgomery County to develop programs to address landscaping and signage throughout the county. The program was likely inspired by First Lady Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson’s creation of the Committee for a More Beautiful Capital, but the Montgomery Committee had no enforcement powers or authority regarding zoning matters. However, it staged a “beautification rally” in the parking lot of Wheaton Plaza in October 1965 and conducted a tour of Montgomery County’s shopping centers in 1966, specifically citing the Glenmont Shopping Center as “trashy in appearance” with “promiscuously placed signs” and “no design value;” moreover, the shopping center was surrounding by “an eyesore” of a parking lot. Different ownership of each area or store of the shopping center meant that there were little, if any, signage or storefront guidelines for each shop to follow, resulting in a plethora of competing advertisements, signs, and storefronts; the effect was reminiscent of the unpleasant, haphazard strip of disjointed stores along Georgia Avenue in Silver Spring in the 1930s. Even the Glenmont Arcade’s emphasis on uniform storefronts and an inward-focused commercial space was not seen as an exemplary retail environment as the earlier Chevy Chase Arcade had. Instead, the Arcade in combination with its surrounding stores was seen as suburban blight compared to the nearby marble-floored, pastel-painted Wheaton Plaza. The Glenmont Shopping Center was the antithesis of the ideal shopping experience.

This negative view of the shopping center has persisted into the present as plans for redevelopment of the area immediately surrounding the 1998 metro station have moved forward. The January 2012 Glenmont Sector Plan, written by the Montgomery County Planning Department, described the shopping center as having “a poor vehicle circulation pattern, inadequate pedestrian facilities, and a low aesthetic value.” While the plan cites hopes of redeveloping the shopping center and perhaps retaining portions of the Glenmont Arcade and Shopping Center, this could prove difficult given the thirteen different owners of different portions of the shopping center. Several local residents, including Kris Kumaroo, the founder and former president of the Greater Glenmont Civil Association, feel that the shopping center lacks architectural merit and should be completely redeveloped; owners and developers should “start it over.”

“Googie” and “Exaggerated Modern” Architecture

While the earliest shopping centers of the 1920s relied on historicist styles to mask the commercial nature of their shops and the shopping centers of the 1930s and 1940s often employed the graphic, automobile-oriented banding and curved corners of Streamline Moderne, by the 1950s, the shopping center itself no longer needed to function aesthetically as a local landmark. Shopping center design shifted toward utility as economic studies declared design flourishes as superfluous and of little aid in increasing profits. It remained important to focus on uniformity and landscaping throughout the plaza to maintain a comfortable, domestic feel, but advertising and signage, particularly near or beyond large parking lots, became increasingly important. While the Glenmont Shopping Center provided little in the way of uniformity or landscaping, the brightly colored, “Googie” neon sign over the arcade portion of the center spoke to a desire to move beyond the bare basics of signage and attract the passing motorist.

“Googie” architecture, or “exaggerated modern” as it is sometimes known, originated in suburban California in the 1950s and 1960s as an answer to the problems of automobile-oriented architecture and out of changing aesthetics of the late 1950s. Characterized by large, colorful, irregularly-shaped signage, unusual roof forms, and the influence of space-age technology, the style was critiqued by many because of its overtly commercial nature and its “corrupted versions of high-art designs.” The over-the-top, euphoric style mimicked the era’s exuberance of consumption as new technologies and products became within reach of middle-class spending. Just as objects that had previously been seen as luxuries turned into necessities, so too did the design of products, shifting from streamlined, efficient styles design to the lavish, almost gaudy colors and materials of “exaggerated modern.”

Although signage had long played an important role in commercial architecture, the irregular forms, bright colors, and exaggerated shapes were neither classically- nor traditionally-inspired, nor did they follow Modernism’s main tenet of the avoidance of applied ornament. Critics were unsure of how to classify the “exaggerated modernism” of coffee shops and drive-in restaurants, or if they were even worthy of being examined at all. However, “Googie” architecture was inspired by genuine optimism and a belief in technical progress and the future. Forms were meant to appear as though they defied gravity entirely, like the airplanes and spacecrafts of the postwar era. Architectural critic Douglas Haskell wrote an article for House and Home in 1952 about the style, describing elements that appeared to “hang from the sky;” it was, he declared, “an architecture up in the air.”

The style was further influenced by two international exhibitions, the Seattle Century 21 Exposition (1962), with Seattle’s Space Needle representing the zenith of human abilities, and the New York World’s Fair’s (1964) Unisphere, Space Park, and General Motors “Futurama II” exhibit. The General Motors pavilion in particular evoked the ethereal abilities of architecture and technology, greeting its visitors with a huge, sweeping entrance building whose curved form and hovering canopy resembled an airplane wing. The international fairs, while celebrating the futuristic “Googie” style, simultaneously marked the beginning of its demise as people began to view its shapes and implied modernity as empty and naïve. The American dream of living in suburbs and owning a car, the epitome of middle-class comfort, had already been achieved, and the realities of race and gender inequality had been brought to the forefront of American culture.

The simple canopy of the Glenmont Shopping Center, while not as architecturally sophisticated as the designs of the international exhibitions, intended to produce the illusion of floating signage and roofs through cantilevers and small metal piers. The canopy above the arcade portion of the shopping center is even more dramatic than that of the surrounding stores, protruding out further and higher. The signage above also suggests a playfulness and lightness through a mixing of color choices (canary yellow, bright blue, and red contrast with a black background) and floating diamonds and rectangles. Easily visible from several hundred feet away, it is perhaps this signage, along with that of the rest of the shopping center, which caused the members of the Committee for a More Beautiful Montgomery County to refer to the Glenmont Shopping Center as “flashy” and “trashy.”

The Rise and Fall of Bowling Alleys

Regardless of early opinions on the aesthetics of the shopping center, the opening of Glenmont Lanes provided a source of entertainment for the local community and was representative of the nation-wide bowling craze of the 1950s and 1960s. Early versions of modern bowling are believed to have originated in Germany sometime in the Middle Ages and spread to other northern European countries, arriving in the United States via colonial settlers. The influx of thousands of German immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s popularized the sport, leading to the formal standardization of bowling balls and lanes with the establishment of the American Bowling Congress in 1895.

Although bowling experienced a short-lived popularity with the upper-class in the late nineteenth century, its frequent locations in saloons patronized by all-male working-class immigrants ultimately associated the sport with alcohol, gambling, and illegal activity. Furthermore, basement locations of alleys in order to save space on upper floors for those not interested in playing meant poor lighting, sanitation, and ventilation. Prohibition in the 1920s, however, demanded the isolation of bowling alleys from the newly-illegal bars and saloons they were formerly situated in, and reformers attempted to improve the sport’s reputation and make it more appealing to women through aesthetic improvements. While many women did begin bowling in the 1920s and 1930s, it was not until World War II that women began bowling in greater numbers, typically as part of an “industrial” team, much like the popular male teams before the war. These “industrial” teams were partially subsidized and organized by employers, usually large manufacturing companies, as a way to foster stronger worker-manager relations. The lower cost of bowling and the ease of joining a team with friends and coworkers aided greatly in the popularization of the sport among both sexes of the middle-class.

Despite increased female bowling during and after the Second World War, however, it was difficult to market bowling as a family sport, largely due to the presence of pinboys who shuttled back and forth behind the pins in alleys, setting up the pins and returning the bowling balls to the players for the next frame. The low wages, demanding physical labor, and possibility of injury on the job attracted only the most unskilled of workers, typically young boys or migrants. Author Andrew Hurley asserts that pinboys and their generally surly attitude were the single most important factor detracting from the public view of bowling as a wholesome sport, and the invention of the automatic pin-setter in the 1950s revolutionized the industry. New bowling alleys sprang up in ever-expanding suburbs, using not only modern, automated machinery but also up-to-date, attractive design that “conformed perfectly to the aesthetic of glitz that was coming to dominate the commercial thoroughfare of suburbia.” By adopting middle-class commercial aesthetics, bowling alleys were then physically and visually acceptable in suburban neighborhoods.

By the late 1950s, over 9,000 bowling establishments could be found in the United States, with nearly a quarter of these establishments constructed between 1952 and 1958. In the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area alone, there were over 900 bowling establishments with some 100,000 participants by 1958. Most popular in the D.C. area was duckpin bowling, a regional version of regular ten-pin bowling in which the pins are shorter and squatter and the ball is smaller and without a hole. Trade publications declared that shopping centers, particularly those near middle-class suburbs, could benefit financially from including a bowling alley in their plans and could also easily accommodate the noise, lighting, and traffic of a bowling alley. As shopping centers took on an identity similar to a local community center or meeting place, the addition of a bowling alley only fortified this concept by frequently providing the space for group meetings. The Women’s Club of Silver Spring, for example, frequently met at Glenmont Lanes in the early 1960s; presumably, its use as a community hub decreased as the shopping center’s reputation did.

Despite the industry’s attempts in the 1950s and 1960s to appeal to families and a younger generation of bowlers, by the mid-1960s, the bowling boom had ended. The popularity of the sport (particularly among older players) continued into the 1970s and early 1980s, but by the late 1980s, it became clear that new bowlers had not been attracted to the sport, and establishments were forced to close as revenues decreased. The decline of bowling alleys, both ten-pin and duckpin, continued into the 1990s and early 2000s, including the closure of Tuffy Leemans’ Glenmont Lanes in 2002.

Washington, D.C. Post- WWII Suburban Development

Montgomery County had long been a place of refuge from city life before its post-World War II emergence as home to hundreds of thousands of suburban residents. Following the end of the Civil War, the population of Washington, D.C. grew significantly, and with it came the desire to escape the heat, filth, and congestion that plagued the city in the summer. The wealthy built summer residences in southern Montgomery County, particularly after the 1873 opening of the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad’s Metropolitan Branch, which ran between Washington, D.C. and Point of Rocks, Maryland. Although the option of public transportation made access to certain parts of the county easier, the cost of commuting in and out of the city was prohibitive for all but members of the upper class.

While the opening of several streetcar lines and increased automobile ownership in the 1920s changed this, it was not until the population growth of the metropolitan area due to increased federal employment in the 1930s that southern Montgomery County saw significant development. Suburban communities sprang up near earlier streetcar suburbs, and widespread use of the automobile in the 1930s and 1940s also facilitated the expansion of development into formerly rural farmlands. Montgomery County was seen as "a place for rest, refreshment and a retreat from the cares, noise and stress of the city and the world in general." The end of World War II and the subsequent housing shortage in the Washington, D.C. area furthered residential development, predominantly in planned subdivision communities of single-family detached houses. Up until the 1950s and 1960s, most of this development was focused near Silver Spring and Bethesda/Chevy Chase, but following a dip in real estate sales as the market near the district line became saturated in the mid-1950s, growth moved northward towards Wheaton, Glenmont, and Rockville. Wheaton-Glenmont was believed to be the fastest-developing area in Montgomery County in 1959.

This second wave of building was distinct from the residential developments created immediately following World War II, which were mostly mass-produced and sold for under $10,000 with federal aid financing mortgages. After 1955, however, changes in the funding of federal mortgages made banks reluctant to take on the low mortgage rates offered through the Veterans Administration, and developers began to build larger but still traditionally-inspired houses selling for more than $20,000 – projects that would not have qualified for federal aid. Development slowed in the 1970s and 1980s, but the opening of the Glenmont Metro Station in 1998 has called for redevelopment plans of the Randolph Road and Georgia Avenue crossing, threatening the future of the Glenmont Arcade and Shopping Center.

Architectural Information General Statement:

Architectural character:

Since its construction in 1958-1960, the Glenmont Arcade and surrounding stores of the Glenmont Shopping Center have provided shopping and entertainment for the nearby suburban community and attracted passing automobiles with its openly commercial, if not unified, advertising and architecture. A large front parking lot accommodates several hundred cars, a flat overhead canopy shields customers from the elements, large plate-glass windows with simple metal framing members and brick surrounds clearly display goods and services, and a large neon sign advertises the shopping center day and night. The Arcade portion of the shopping center provides an almost indoor shopping experience with individual shops opening out to a covered central circulation space; the rest of the shopping center faces the parking lot and thus markets itself to passing motorists at the traffic intersection. However, uncoordinated signage, construction seams, and material changes across store facades due to distinct ownership of different parts of the shopping center produce a cluttered and disorganized appearance. Additionally, like many other shopping centers and vernacular commercial buildings, original storefronts, signage, and shop interiors have been modified to accommodate new tenants and uses. The ground floor of the Glenmont Arcade, however, retains much of its historic fabric, including original door and window hardware, neon signage, polished linoleum flooring, light fixtures, and the overall layout of storefronts.

Condition of fabric:

Good

Description of Exterior:

The main façade of the shopping center is divided into roughly four different parts: the former Grand Union supermarket (now a Staples), the former Peoples Drug Store (today a CVS), a group of five storefronts adjacent to the former drug store on the east, and the Glenmont Arcade. All are constructed of common bond or American bond brick storefronts with large plate glass windows and metal framing members. Each storefront is slightly different due to continued independent ownership from surrounding shops.

The earliest building of the shopping center, the former supermarket (currently Staples), is constructed of American bond brick with a large central entrance. The bricks vary in color, particularly in the header courses, where a blue-gray brick is occasionally used in place of red brick. Much of the original glazed façade has been replaced by an entirely different color of terra cotta-red American bond brick and has been poorly repointed with white mortar. The main entrance to the store is composed of a glass automatic door with red metal framing; on either side of the two doors are two stationary windows flanked by four large windows on either side. A transom window, also framed in the same red metal framing members, rises from the top of the automatic doors to the overhead canopy. The brick façade continues upwards to form a brick parapet, most of which is covered by current signage for the store. Projecting outward over the sidewalk is a flat canopy of metal decking which now forms the base for new corporate signage. The large, tripartite red and white “Staples” sign covers up the arched roof of the former grocery store. This exaggerated parapet is supported by seven square piers of brick and stucco, each approximately a foot and a half square.

To the west of the Staples is a single storefront of plate glass windows and metal framing surrounded by American bond brickwork. The base of the storefront is covered with sheet metal and painted in a trompe l’oeil-style of red brick; this paint treatment continues around the corner and onto the side of the store, where a glass enclosure covers an outdoor staircase to an underground storage space.

Adjacent to the Staples on the east is the former Peoples Drug Store (today a CVS), also clad with a brick and plate glass storefront, however visible construction seams where storefronts meet and slight differences in the types and patterning of the brickwork attest to the individual construction of these stores rather than the unified planning of most shopping centers. The asymmetrical, plate glass storefront and entrance are framed by newer extruded brushed metal framing members and several sets of original metal framing members. American bond brick, painted a matte, terra cotta red, frames the storefront, and roman brick, also painted, runs underneath the windows, forming a base. Much of this roman brick base is now covered with brushed sheet metal to match the newer window frames. The doors of the original entrance, located on the western side of the store façade, have been replaced with sliding automatic doors and a transom that reaches upward to where the canopy extends overhead, as do the windows.

The flat, metal decking canopy that extends out from the CVS storefront is lower than that of Staples and tucks underneath it where the two storefronts meet. While portions of the Staples storefront reveal the red brick parapet behind it and the arch of the former supermarket’s roof, the entire parapet of CVS has been covered by a classically-inspired, white and gray stucco parapet with dentil crown molding and corporate signage. The canopy in front of this store is supported by six slender, round metal columns.

The group of stores adjacent to the CVS on the east are unified by the continuation of the overhead canopy, here supported by six square piers of beige running bond brick. Signs for each of the five storefronts hang down from the center of the underside of the canopy so that they are visible to pedestrians walking under the canopy. Above, the original flat canopy serves as the base of a wide, red-roofed gabled canopy that covers the parapet; the long, flat sides of the gable bear store names in red lettering.

Underneath the canopy, asymmetrical storefronts with different sizes of plate glass windows and doors are all surrounded by American bond blond brick. Several courses of brick, topped with a course of header bricks, act as a base for the storefront windows, which reach up to the canopy. All the storefronts are flat and face into the parking lot, except for that of the current grocery store, whose central entrance is recessed from the sidewalk and whose storefront windows angle inward towards the recessed doorway.